Inspiration

What’s the Difference Between Stocks and Bonds?

In partnership with Acorns

Written by Stacy Rapacon

Updated

Like so many supposed rivals—savory vs. sweet, Magic Johnson vs. Larry Bird, Superman vs. Batman—when it comes to stocks vs. bonds, the real winner is a combination of both. (See: salted caramel mochas, the 1992 Dream Team and The Justice League.)

That’s because their differences complement each other perfectly to create a winning portfolio.

Back up. What exactly are stocks, again?

Stocks are shares of a public company’s assets and earnings. So when you buy stocks, you effectively become part-owner of the company and gain a vested interest in its success or failure. The value of your shares goes up and down with the company’s financial well-being (or rather with investors’ perception of that company’s well-being, as reflected in share price). So they stand the chance to soar and give you great returns, or sink and bring you losses.

Indeed, between 1926 and 2017, a portfolio built of 100 percent stocks offered a healthy average annual return of 10.3 percent, according to data from financial firm Vanguard. But it wasn’t smooth sailing throughout the years. The portfolio suffered its worst year during that time period in 1931 with a heavy loss of 43.1 percent. Then, it had its best year in 1933, gaining a whopping 54.2 percent.

Put simply: Stocks are risky, but can be very rewarding over the long run.

And what are bonds?

When you invest in bonds, you’re essentially giving a loan to an institution. And the corporation, government or other entity you’re lending to is promising to pay you back—with interest—by a specified time. That means bonds are relatively safe, as long as the entity doesn’t go belly up.

But there’s a tradeoff for the added safety. Over the same time period mentioned above, the average return for a 100-percent bond portfolio was just 5.4 percent, about half as much as the all-stock portfolio. Its worst year during that period was in 1968 when it lost 8.1 percent. Its best year was in 1982 when it gained 32.6 percent. Clearly, bonds offer lower risk, but also lower rewards.

Got it. So, bonds are safer than stocks. Right?

It’s a bit more nuanced than that. Some bonds come with greater risks—and higher yields—if the issuers are considered less dependable, in terms of how likely they are to pay investors back as promised. Similarly, the levels of risk and reward can vary greatly among stocks. For example, small companies tend to have greater potential for growth—and higher risk of loss—while large companies typically are more stable. So some high-risk “junk bonds” can actually be riskier than some high-quality stocks, which might even be able to supply some bond-like income with dividends.

To gauge the risk level of a bond, you can check reports from ratings agencies that grade issuers’ creditworthiness and predict whether they’ll be able to honor their debts. Moody’s rates the least risky bets as Aaa and the riskiest entities as C; Standard & Poor’s and Fitch Ratings grade from AAA to D.

For stocks, determining risk can be a bit more complicated, and many experts do it differently from one another. One popular measure of risk is a stock’s beta, which indicates how much its share price moves up and down in a given period of time compared with the market’s movements. The market has a beta of 1, so if a stock has a beta higher than 1, that means that its price has been more volatile than the market and is likely to be a riskier bet. Another measure of risk is a stock’s alpha, which represents how much better or worse it performed compared with its benchmark. So a stock with an alpha of 3 beat its benchmark by 3 percent while a -3 indicates that it lagged its benchmark by that much. (A benchmark is typically a broad-based index like the S&P 500 or an index of stocks in that sector.) You can also determine a stock’s risk more qualitatively by simply asking yourself—and tapping expert analysis to determine—whether you think the company is well-positioned to bring in enough profits to succeed or whether it faces headwinds that might hinder its profitability.

All those nuances aside, though, yes, the general thinking is that stocks equal aggressive investing and bonds skew more conservative.

So how do stocks and bonds work well together?

You can balance your risk levels and rewards potential by investing in a mix of stocks and bonds that suits your financial goals, risk tolerance and time horizon. For example, if you’re still decades away from when you hope to achieve a particular goal (like retirement), you can afford to be aggressive because you have plenty of time to recover from any inevitable drops you’ll experience along the way. In that case, an asset allocation of 80 percent stocks and 20 percent bonds might work well for you. According to Vanguard, a portfolio with that mix returned 9.6 percent a year, on average, from 1926 through 2017, with its best year delivering a return of 45.4 percent and its worst year shedding 34.9 percent.

If that’s too much risk for you to stomach, or you need to be more conservative as your target date approaches, you might prefer a more balanced asset allocation, going straight-up halfsies between stock and bonds. Such a 50/50 portfolio returned 8.4 percent a year, on average, for the same period, according to Vanguard. Its top-performing year saw a gain of 32.3 percent while its worst-performing year brought a loss of 22.5 percent.

Once you’re within the final few years of achieving your goal—or in the case of retirement, even once you’re actually retired—you may want to cut way back on the risk portion of your portfolio. At the same time, you still want your investments to grow and beat inflation, so you may not want to rid yourself of stocks completely. So flipping to an asset allocation of 20 percent stocks and 80 percent bonds might make sense. This portfolio returned an average 6.7 percent a year from 1926 through 2017, according to Vanguard, with its best year returning 29.8 percent and its worst year losing 10.1 percent.

Whatever your own long-term financial goals, you need a well-diversified portfolio to help you achieve them. And that smart diversification is likely to include a fitting combo of both stocks and bonds.

* Investing involves risk including loss of principal. This information is provided for educational use only and is not a recommendation to buy or sell any specific security or invest in any particular strategy.

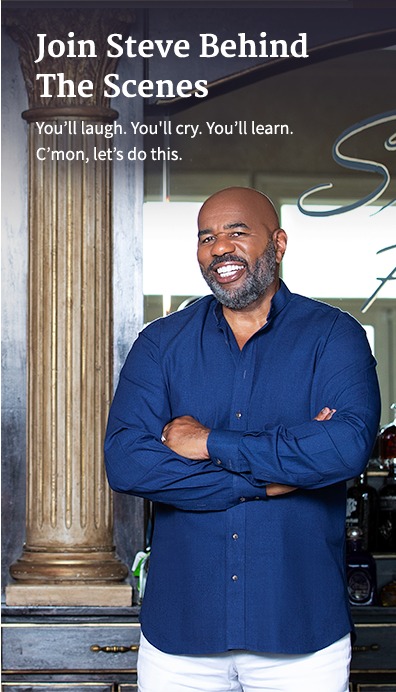

For more information visit: https://www.acorns.com/steveharvey/

More like this